Treatment for Pneumonia: Options, Recovery, and When to Seek Care

How Pneumonia Is Treated: Principles, Pathways, and a Quick Roadmap

Pneumonia can range from a stubborn home-managed illness to a life-threatening emergency, and treatment decisions hinge on severity, cause, and your personal health profile. At its core, therapy aims to fight the underlying infection, keep oxygen moving comfortably through the lungs, and prevent complications like sepsis or fluid buildup. Public health authorities consistently rank lower respiratory infections among the leading reasons for hospital admission worldwide, especially in older adults, infants, and people with chronic heart, lung, or immune conditions. Understanding how clinicians think through treatment helps you know what to expect—and when to ask for more help if recovery feels stalled.

Here’s the roadmap this article follows so you can jump to what matters most:

– Foundations: how clinicians decide on treatment and why speed matters for certain infections

– Medicines: antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals—what they do and when they’re used

– Supportive care: oxygen, fluids, fever control, airway clearance, and rest pacing

– When to seek care: red flags, home vs. hospital decisions, and common tests

– Recovery: timelines, setbacks, prevention steps, and follow-up planning

Treatment usually starts with a careful history and exam: recent sick contacts, sudden chills or gradual onset, exposure risks, and comorbidities guide the initial plan. Clinicians often begin empiric therapy—treatment aimed at the most likely culprit—while tests are pending. If bacteria are suspected, antibiotics are started quickly; if a viral cause such as seasonal influenza is likely and symptoms are early, an antiviral may be considered. Supportive care runs alongside targeted medicines: oxygen keeps levels adequate while lungs heal; fluids maintain blood pressure and loosen secretions; fever reducers bring down inflammation so you can breathe and rest better; and breathing exercises encourage lung expansion.

Think of recovery as a relay, not a sprint. The first lap focuses on stabilizing oxygen and temperature. The next lap aims to reduce cough intensity and clear mucus. The final lap tackles fatigue and rebuilds stamina. Along the way, your care team might change course based on test results, side effects, or how your symptoms evolve. That flexibility is not a sign of failure—it’s a sign your treatment is being tailored to you, which is exactly the point.

Targeted Medicines: Antibiotics, Antivirals, and When They’re Used

Choosing the right medicine depends on what’s causing the pneumonia and how sick you are. Bacterial pneumonia often needs antibiotics, while viral pneumonia does not. Because tests can take time, clinicians may start antibiotics when the history, exam, and imaging strongly suggest bacteria. Once lab results clarify the culprit—or show a viral pattern—medications can be narrowed, switched, or stopped. Comparing the options helps explain why plans differ from person to person.

Antibiotics (for suspected or confirmed bacterial causes) are the mainstay for many community-acquired cases. Oral antibiotics are common for stable patients at home; intravenous antibiotics are used in the hospital when absorption is uncertain or illness is severe. Duration typically runs 5–7 days for uncomplicated cases that show clear improvement within the first 2–3 days; more severe disease, slow response, or complications may require longer. Key considerations include allergies, kidney or liver function, interactions with other medications, and local resistance patterns. Monitoring is essential: if fever, breathing, or chest discomfort are not improving after 48–72 hours, clinicians reassess the diagnosis, the organism, and whether complications are emerging.

Antivirals play a role when a specific virus is suspected and the timing fits. For seasonal influenza, early treatment—ideally within 48 hours of symptom onset—can modestly shorten illness and reduce complications, especially in high-risk groups. For other respiratory viruses, options vary by region and risk category, and eligibility often depends on age, underlying conditions, and the time since symptoms began. Importantly, antibiotics do not treat viral pneumonia; using them when not needed offers no benefit and can cause side effects or resistance.

Antifungals are reserved for select situations—typically in people with weakened immune systems, chronic lung disease, or those with relevant environmental exposures. Because fungal causes are uncommon in otherwise healthy adults, these medicines are targeted only when tests or risk factors justify them.

What about add-on therapies? Corticosteroids are not routine for community-acquired pneumonia, but may be considered in specific scenarios under specialist guidance, such as refractory septic shock or certain severe presentations. Bronchodilators can help if underlying airway hyperreactivity or wheezing is present. Cough suppressants may be used sparingly to protect sleep, though keeping some cough helps clear mucus. A few practical points to keep in mind:

– Finish prescribed courses unless your clinician advises a change

– Report side effects early, especially rashes, severe diarrhea, or dizziness

– Avoid leftover or shared antibiotics; using the wrong drug or dose delays recovery

Supportive Care That Speeds Healing: Home Strategies and Hospital Tools

Targeted medicines treat the cause, but supportive care often determines how comfortably and completely you recover. At home, think about four pillars: oxygenation, hydration, temperature control, and airway clearance. In the hospital, the same pillars apply—with more tools, close monitoring, and rapid escalation if breathing or blood pressure wobble.

Oxygenation: If you own a home pulse oximeter, many clinicians aim for readings in the mid‑90s for otherwise healthy adults; lower personalized targets may apply for chronic lung disease. If numbers drift down or you feel suddenly breathless at rest, it’s a signal to seek care. In hospital settings, oxygen may be delivered by nasal cannula or mask, and settings are adjusted to keep levels safe while avoiding excess.

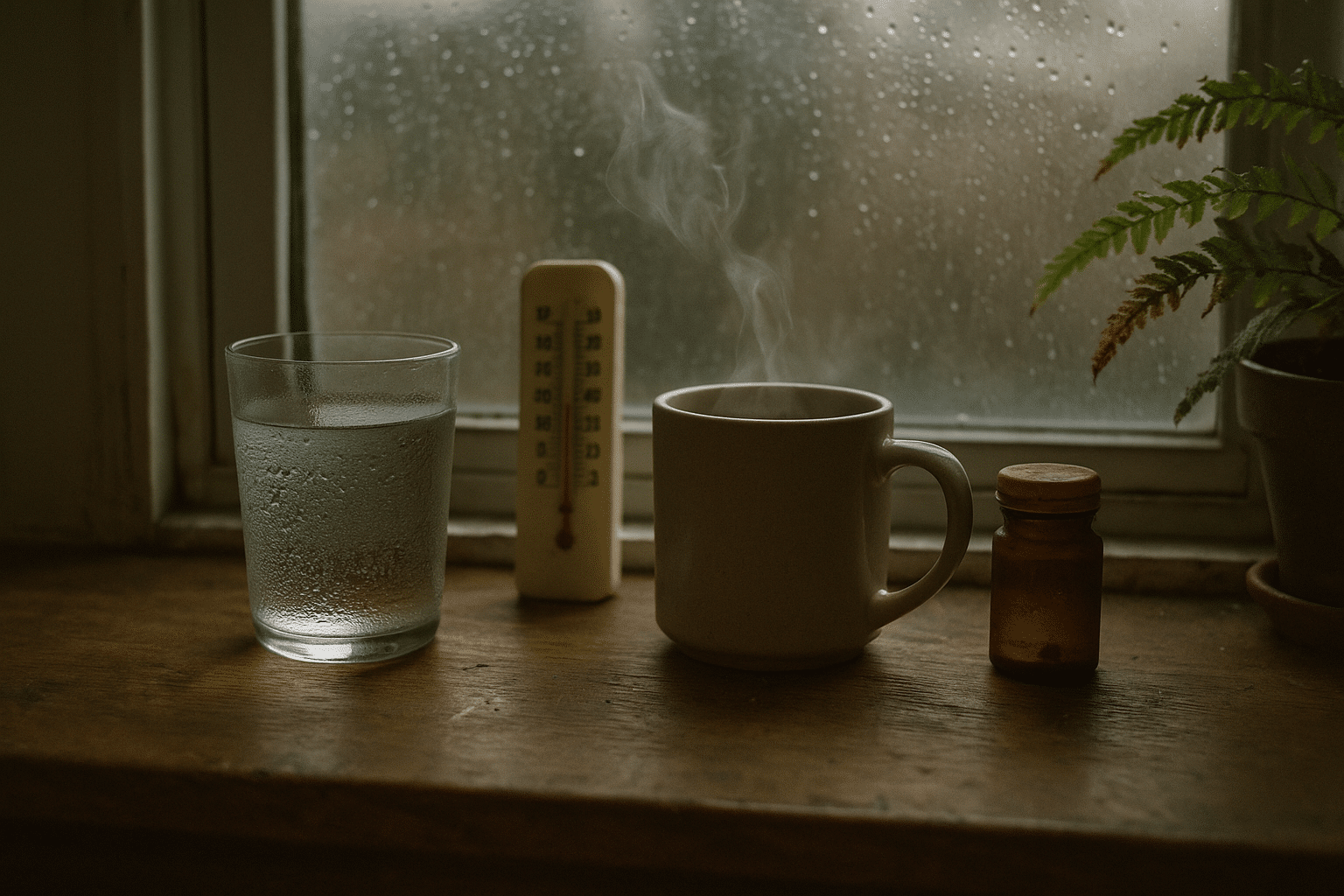

Hydration and nutrition: Fluids thin mucus, support blood pressure, and ease headaches. Sipping warm liquids can soothe the throat and help coughs be more productive. Small, frequent meals may beat large plates when your appetite dips. Salt balance matters in some conditions, so ask for guidance if you have heart or kidney disease. Fever, faster breathing, and sweating can increase fluid needs; watch urine color—it should be pale, not deep amber.

Temperature and pain: Fever can be managed with rest, cooling measures, and fever reducers such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen (if appropriate for you). Aim for comfort, not absolute zero fever; a gentle reduction often improves breathing and sleep. Chest wall soreness from coughing is common—warm compresses and careful positioning with extra pillows can help.

Airway clearance: Your lungs are like bellows—expansion helps move secretions. Try gentle breathing exercises: inhale slowly through the nose, hold a moment, and exhale through pursed lips. Short walks or room‑laps can mobilize mucus without overexertion. A humidifier adds moisture, but keep it clean to avoid mold. Practical tips:

– Pace activity: short, frequent bursts are often better than long pushes

– Use a “cough log” to track when coughs are most productive and time airway clearance then

– Elevate the head of the bed to ease nighttime breathing

– Avoid smoke and irritants; fresh, cool air can be calming

Hospital tools layer on support: intravenous fluids if dehydration or low blood pressure creep in; respiratory therapy to coach breathing techniques; frequent checks of oxygen saturation and vital signs; and imaging or blood tests if recovery stalls. The goal is to catch complications early—pleural effusions, worsening inflammation, or heart strain—so treatment can pivot quickly. Supportive care may sound simple, but it’s often the quiet work that helps the fog lift sooner.

When to Seek Care: Red Flags, Tests, and What Clinicians Look For

Knowing when to ask for help can be lifesaving. Seek urgent evaluation if you notice any of the following:

– Blue or gray lips or fingertips, severe breathlessness at rest, or confusion

– Chest pain that worsens with breathing, coughing, or movement

– Oxygen saturation below a clinician-advised threshold (often under the low‑90s for many adults) if you have a home oximeter

– A high fever that persists beyond 3 days, or fevers that return after a brief lull

– Signs of dehydration: very dark urine, dizziness, or inability to keep fluids down

Children need special attention. Call for care if breathing is fast or labored (nostrils flaring, ribcage pulling in), if there are long pauses between breaths, if feeding is poor, or if fewer wet diapers point to dehydration. Pregnant individuals, older adults, and people with chronic heart, lung, kidney, liver, or immune conditions should have a lower threshold to seek care.

In clinics or hospitals, clinicians assess severity and tailor treatment. They may use scoring tools that weigh mental status, breathing rate, blood pressure, and age to help decide on home vs. hospital care. Common tests include a chest X‑ray, pulse oximetry, and basic blood work to gauge inflammation and oxygen‑carrying capacity. Sputum cultures or swabs can identify organisms and guide targeted therapy; not everyone needs these tests, but they’re useful when the cause is unclear, illness is severe, or early treatment isn’t working as expected.

Imaging helps differentiate pneumonia from look‑alikes like heart failure, clots, or inflammatory lung diseases. If complications arise—fluid around the lungs, areas of collapse, or persistent fevers—your team might order repeat imaging or ultrasound to guide next steps. Comparatively, outpatient care focuses on frequent check‑ins, symptom tracking, and ensuring medications are tolerated, while inpatient care emphasizes continuous monitoring and access to respiratory support.

If you’re unsure whether to go in, consider a “tipping point” checklist:

– Breathing feels harder by the hour rather than better by the day

– You cannot keep fluids or medicines down

– Lightheadedness or confusion appears or worsens

– Home oxygen readings persistently stay low

When in doubt, err on the side of safety and seek timely care.

Recovery Timeline, Prevention Steps, and A Practical Wrap‑Up

Recovery from pneumonia is often steady but not linear. Many people notice fever and breathing improve within a few days of starting effective therapy, yet cough and fatigue can linger for weeks. A common pattern is: days 1–3, fevers settle; days 4–7, energy returns in spurts; weeks 2–4, cough gradually softens; weeks 4–8, stamina normalizes. Setbacks happen—overexertion, poor sleep, or another virus can nudge symptoms back for a day or two. Gentle pacing, good hydration, and consistent airway clearance are your allies.

Follow‑up matters. If symptoms are slow to improve, worsen after initial gains, or if you’re in a higher‑risk group, clinicians may schedule a recheck or repeat imaging to confirm recovery. Some adults—especially those with a history of heavy smoking, immune concerns, or persistent symptoms—may be advised to have a follow‑up chest X‑ray several weeks after illness to ensure everything has resolved. Medication adherence is crucial: take antibiotics and antivirals exactly as prescribed, and report side effects early so adjustments can keep you on track.

To reduce future risk, layer prevention into daily life:

– Stay up to date on recommended vaccines, including influenza and pneumococcal options when eligible

– Wash hands regularly and avoid close contact when respiratory illnesses are circulating

– Ventilate indoor spaces; a few minutes of fresh air can lower germ load

– Maintain sleep, nutrition, and activity habits that support immune function

– Manage chronic conditions proactively; good control reduces complications if you do get sick

Home readiness also helps: a working thermometer, a pulse oximeter if advised, fever reducers you tolerate, and a simple plan for fluids, rest, and check‑ins. If you live alone, arrange a daily call or message with a friend or family member during the first week of illness. Think of these tools as a safety net that lets you focus on healing rather than logistics.

Conclusion: Pneumonia treatment works best when it’s personalized—matching the likely cause with the right medicine, pairing that with steady supportive care, and adjusting based on how you feel each day. If breathing worsens, fever returns, or you feel uneasy about your progress, reach out early. With a clear plan, realistic expectations, and timely follow‑up, most people move from short walks to long ones, one careful breath at a time.